I know I’ve been absent without leave for a long time, but I’m coming back because at Melissa’s urging, I’ve been reading The Profile Makers by Linda Bierds. I’m probably biased because Bierds so often seems to do so dazzlingly exactly what I try to do in my own poems but do somewhat less dazzlingly. I realize it’s a project that doesn’t interest many people at all, although those may be the sort of cynics who walk into Chartres Cathedral and say, “This God stuff is so yesterday’s news. Been there done that.”

As I’ve said before, I am always struck by poems with wheels within wheels of imagination. In “The Ghost Trio” by Bierds, for example, the poet imagines herself as Erasmus Darwin (grandfather of Charles) imagining a painting he’d once seen of ice skaters and imagining how the skate blades would look to imagined fish below in the imagined ice in the imagined painting in the imagined world of Erasmus Darwin—and indirectly imagining how Charles Darwin’s vision might have evolved from his grandfather’s imagination.

Perhaps they are stunned

by the strange heaven—dotted with

boot soles and chair legs

and are slumped on the mud-rich bottom—

waiting through time for a kind of shimmer,

an image perhaps, something

known and familiar, something

rushing above in their own likeness,

silver and blade-thin at the rim of the world.

Sometimes when imagination is fully realized, it seems there’s nothing more to ask of a poem. Any “epiphany” would be superfluous, as the simple act of immersing yourself so completely in the quiet winter of 1748 is already as meaningful and dramatic as, say, Juliet’s suicide: “This is thy sheath; there rust.”

Bierds’ poem “Balance” is about L.J.M. Daguerre, inventor of the daguerreotype, but only refers to photography briefly at the start of the poem: “before time balanced / on a silver plate.” The rest of the poem is about Daguerre as a youth balancing on a tightrope, his inevitable falls, and how the world looks to him on his back on the flagstone streets as he looks up at “the rooflines and eaves, / all the doves in their darkening chambers.” That image of “all the doves in their darkening chambers” suggests so exquisitely how the experience led him to photography. The earlier reference to “time balanced on a silver plate” seems almost superfluous. Daguerre was in theater when young so my guess is the poem is biographically accurate, but it’s wonderful to think that Bierds might have invented the whole tightrope-walking period of his life.

Bierds’ poem “Shawl: Dorothy Wordsworth at Eighty” describes Dorothy and her brother William coloring eggs as children, when suddenly violence enters the poem. Typically, it’s not anything Dorothy experienced but something she was told:

Once, I was told of a sharp-shinned hawk

who pursued the reflection of its fleeing prey

through three striations of greenhouse glass:

the arrow of its body cracking first into anteroom,

then desert, then the thick mist

of the fuchsias. It lay in a bloodshawl

of ruby flowers, while the petals of glass

on the brick-work floor repeated its image.

Again and again and again.

As all we have passed through sustains us.

who pursued the reflection of its fleeing prey

through three striations of greenhouse glass:

the arrow of its body cracking first into anteroom,

then desert, then the thick mist

of the fuchsias. It lay in a bloodshawl

of ruby flowers, while the petals of glass

on the brick-work floor repeated its image.

Again and again and again.

As all we have passed through sustains us.

What amazing language: “the thick mist / of the fuchsias”! What an amazing image! “As all we have passed through sustains us” seems unnecessary. What is wonderful is how the final image echoes another image repeated throughout the book: how the glass plate negatives of Mathew Brady’s “lesser” Civil War photos were used as greenhouse windows.

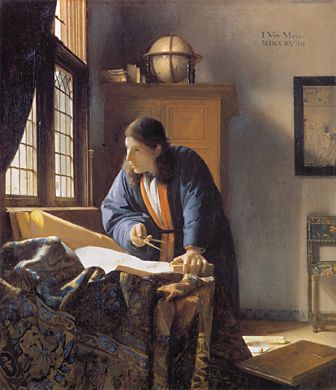

I’m still left with the question of whether imagination by itself can ever be enough. When I read a poem like “The Geographer”—“They are burning the flood fields—such a hissing, hissing, / like a landscape of toads”—it seems it could be. The poem imagines what the geographer in Vermeer’s painting sees outside his window, and also imagines how what he sees is colored by his heart disease: “When the flood waters crested, dark coffins / bobbed down through the cane stalks like blunt pirogues.” Sometimes imagination is wedded to such a passionate compassion that there’s nothing more to ask of a poem.